Digital art for a planet on fire

In 2019, The Shift Project, a French think tank advocating the shift to a post-carbon economy, estimated that the digital sector was responsible for 4% of greenhouse gas emissions if you take into account the life cycle of devices used. This is similar to the amount produced by the airline industry globally before the pandemic. The digital pollution -which keeps on growing- is obviously not compatible with the Paris agreement’s goal to limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius.

Transmitting and viewing online video -a popular activity during the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021- account for a large portion of these emissions. The Shift Project calculated that a quarter of the videos watched online are porn.

In 2019, the digital has consumed roughly 10% perhaps even more of world electricity. Some of that electricity relies on burning fossil fuels. These figures vary depending on where in the world you are. Unsurprisingly, Internet users in Europe or in the US will have a disproportionately large footprint.

The energy necessary to power our online activities is only the tip of the iceberg. The sheer physical and geological dimensions of digital technologies are staggering. Even a single email exchange requires smart devices but also a network of heavy infrastructures made of undersea cables, data centres, exchange points, antennas, routers and other elements of hardware and software. Each of these physical actors of the digital is the result of massive extraction of minerals, appropriation of water and other natural resources, highly polluting chemical processes, social injustice and -further down the line- poor management of e-waste. No matter how “green” Bezos and Zuckerberg claim their data centres are, the wind turbines and solar panels they boast about still require minerals that are neither infinite nor the result of sustainable mining operations.

How do digital artists position themselves in front of these challenges? How do the most ecologically-minded among them navigate the ambivalence of investigating ecological problems while using instruments that potentially contribute to making some of these problems worse? How do they question technosolutionism and the myth that humanity will not have to make any substantial efforts in order to enjoy both infinite growth and a healthy planet?

A crucial strategy adopted by some artists consists in using the digital to materialise otherwise intangible or hidden phenomena such as the carbon footprint of a visit to a famous search engine.

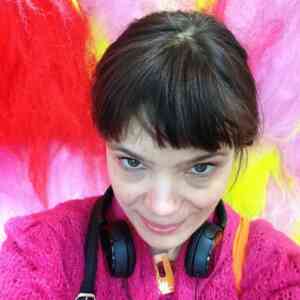

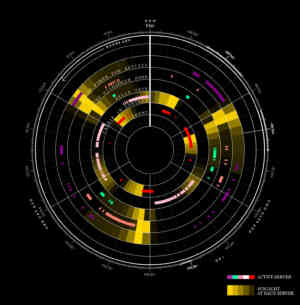

Artist, lecturer and researcher Joana Moll is one of the first artists who made the ecological impact of digital technology clear and easy to understand for all of us. Her web-based piece CO2GLE, for example, makes visible how energy-intensive the internet is. The work calculates the amount of emission derived from the global visits to Google.com per second. A follow-up to this first foray into the physical dimensions of the search engine, DEFOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOREST visualises the average amount of trees that we would need every second in order to absorb the emissions derived from the global searches on google.com: 23 trees per second on average.

Both works present an estimation rather than an accurate computation. Quantifying the environmental footprint of our data is a challenging task: the whole system is massive, complex and not always as transparent as we would like it to be. Still, the point was never to be precise. Rather, the artist wanted to establish a visible connection between our online behaviours and the ecosystems they affect.

Respectively launched in 2014 and 2016, both works were developed at a time when most of us equated digitally with intangibility, a time when no one really gave much thought about the toxic externalities of digital technology.

Her more recent project The Hidden Life of an Amazon User similarly stems from a concern about the heavy environmental footprint of the users’ data collected by tech companies. While buying a book on Amazon, Moll tracked every single interface that the platform made her go through in order to purchase the item. The second layer of that research consisted in intercepting all the codes that made the interactions with the website possible during the purchase. When visiting the online retailer (or any other website for that matter), all the code is downloaded onto the customers´computers which means that part of the energy cost of operating a website falls onto them. Moll then printed out all the code that she had intercepted over the course of that purchase: a massive stack of around 10 000 pages of written code gave weight and visibility to a series of gestures most Amazon Prime users perform mindlessly almost every day.

This artistic project has many layers, just like Amazon has developed many layers of strategies to exploit its users. The e-commerce giant not only makes money out of exploiting user data through the monitoring and analysis of every single activity on its website but it also offloads onto the user a part of the environmental impact and energy cost of its business model.

There’s no negotiation whatsoever at any point in this process.

Other artists experiment with developing protocols and hardware that are less energy & resource-hungry than the ones used by mainstream digital technology.

Solar Protocol, a collaboration between Tega Brain, Alex Nathanson and Benedetta Piantella, is a web platform hosted across a network of solar-powered servers. Because the sun is not shining all day every day, the servers are set up in different locations around the world, coordinating to serve the website from the place enjoying the most sunshine at the time you want to visit that website.

The project investigates how we can reimagine infrastructures to change our relationship with the internet. It combines research, software engineering, hardware design, solar power engineering, community management, data viz and other technologically complex elements but its missions are clear: explore the power of alternative energy and grow into a community of practitioners exploring low-energy digital aesthetics.

What characterises the drive among digital artists to explore ecological issues is not just the formal or technological dimensions of their works, it’s not even the ecological theme either. What matters for many of them is the daily commitment. More and more of these artists are now trying to reduce their carbon footprint; transitioning towards a plant-based diet, cycling, recycling, etc. And of course, taking fewer planes…

Twelve years ago, Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett, the founders of gallery, commons space and online arts-writing platform Furtherfield, were already taking inspiration from Gustav Metzger’s Reduce Art Flights campaign and stopped flying for six months in 2009. Their pledge read: “We will not take an aeroplane for the sake of art. For the next 6 months we will find other ways to visit and participate in exhibitions, fairs, conferences, meetings, residencies. We will not fly for inspiration, nor to appreciate, buy or sell art. But only if 6 others will do the same AND replicate this pledge.”

The pledge (which was followed by 96 other actors of the art world) suggests that changing human behaviour is just as important as finding technical solutions when it comes to making art or simply living within the geological boundaries of our planet.